As we continue to address the question of how similar Texas runaway ads were to those of other states, we have begun focusing on a handful of specific topics within that question. This week we have been working on answering some of the questions we had after the close-reading and initial digital reading of the ads. Daniel and I split up the labour by tackling different questions. Below, find results for the digital reading I conducted on my half of the questions.

Group Runaways?

One of the things I was interested in after completing the close-reading was whether Texas had a higher frequency of group runaway attempts. In TAPoR’s Comparator, a higher occurrence of the plural word “negros” suggests that Texas might have had more multi-person runaway attempts.

19th C. ads seem to have more commonly spelled “negroes” with an “e” however. (Just as a side note, this highlights the importance of checking for variations or abnormalities in spelling when conducting digital research.) Although the raw count for “negroes” is higher in Arkansas, the relative frequency based on document length is higher for Texas, although not by much.

For the word “runaways,” Texas and Arkansas are relatively equal. Just based on these word counts, it is difficult to make a conclusion about group runaways in Texas, but appears that rates of mentions for group runaways in Texas and Arkansas were roughly equivalent.

In comparison to the Mississippi corpus, Texas rates of “negros” and “negroes” are both higher.

However, use of “runaways” is significantly larger in Mississippi.

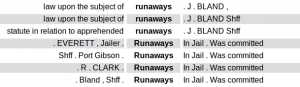

Curious about why this might be, I clicked through to the word in context section.

This snippet from the use of the word “runaways” in the Mississippi ads reveals that it was often used in relation to jailor’s notices. Even more so than other runaway ads, jailor’s notices tend to follow a very standard format, often following a word-for-word form. In Mississippi, many of them are titled “Runaways In Jail” and conclude with a note about the “law upon the subject of runaways,” as seen above. This is one example of how the presence of jailor’s notices in the mix of runaway ads can skew the trends in one direction or another.

Ultimately, the digital reading of the ads through TAPoR suggest to me that Texas did not have a significantly higher frequency of group runaways than either Arkansas or Mississippi. If we choose to pursue this question more closely, it will be necessary to do a combination of digital and close-reading to confirm one way or the other.

Note: For an in-depth explanation of how TAPoR calculates relative frequency ratios, see this earlier post explaining the calculations behind the figures.

Thieves or accomplices?

In my rough-draft of the close-reading of the ads, I noticed that many runaway ads suspect an accomplice of persuading the slave to run away, or a thief of stealing the slave for resale. These ads provide historical clues about some of the routes of aid that runaways might have had, or perhaps, instances in which slaves were made to “run away” against their will. In ads where the subscriber suspects a thief, it is not possible to know whether those suspicions are accurate or not, but it can give us a sense of the climate in that region. If subscribers are more suspicious of thieves or accomplices in one region vs. another, it may suggest a situation of lawlessness and slaveholder fear in that state.

In Texas compared to Mississippi, the word “stolen” appears relatively more frequently, but the word “thief” relatively less frequently.

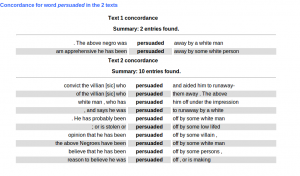

Another word which appears frequently in this category of ad is “persuaded,” which appears more frequently in Mississippi. This screenshot shows snippets of how the word “persuaded” appears in the ads.

To me, these results suggest that the Mississippi ads may have had more instances of accomplice and/or thief suspicions than Texas. Texas and Arkansas had very similar rates for the words “stolen,” “thief,” and “persuaded”.

In Voyant Tools, this embedded word trends from the Telegraph and Texas Register collection shows the correlation between the words “thief” and “stolen”. Both words follow similar patterns across the corpus.

One of the benefits of Voyant is that it allows users to copy an html link to embed Voyant tools into their own blog. Rather than a static screenshot, readers can change the settings on the embedded tool. Try playing around with it!

This tool also allows you to visualize where in the corpus peaks in slave theft occur. Patterns such as these raise questions about why theft might have spiked in the Houston area at that time. This is just one example of how a digital reading can notice patterns difficult to discern through close-reading alone, but inspire further close-reading through the questions raised.

Racial Descriptors? Differences in Racial/Ethnic involvement?

In most runaway ads, the subscriber tends to give some description of the runaway’s complexion or racial status. We were interested in tracking variations in these terms across states. We were also interested in tracking runaway slaves’ involvement with various racial or ethnic groups in their geographical area.

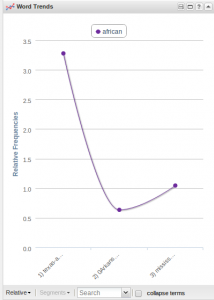

This embedded graph from Voyant shows trends for the words “African” and “Africans” across the Telegraph and Texas Register. Over time, occurrences of these words goes down until eventually disappearing. In class, we talked about potentially finding evidence of the illegal international slave trade continuing for a while in the early years of Texas. These trends would suggest that to be the case.

Additionally, “African” appears most frequently in Texas compared to the other states, and slightly more frequently in Mississippi than in Arkansas. This confirms my suspicions from the close-read that Texas had higher rates of Africans than the other states, as well as my hunch that Mississippi and Texas, with access to ocean ports, would have higher rates of African slaves than landlocked Arkansas.

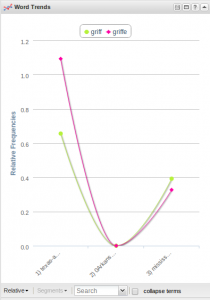

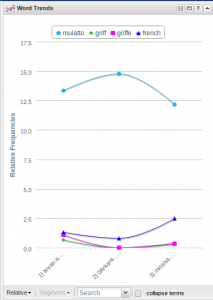

One of the terms we both noticed in our close-readings was the French word Griff(e). “Griff” and “Griffe” occur much more frequently in Texas, followed by Mississippi, and not at all in Arkansas. Tracking the word “Griffe” alongside “French” and “Mulatto” reveals some interesting trends. While Texas and Mississippi have higher use of the word Griff(e), Arkansas has higher use of the word Mulatto. Additionally, Texas and Mississippi — the states where the French word “Griff” is used — also have higher occurrences of the word “French” suggesting a more significant presence of French people or the French language in these states. Possibly, in Texas and Mississippi, subscribers were more likely to prefer the term Griff(e) to refer to someone of part white, part black ancestry, whereas in Arkansas they were more likely to prefer the term Mulatto.

This final screenshot reveals the high relative frequency of “Mexico” and “Mexican” in Texas. In Arkansas and Mississippi, these words never occur at all. This screenshot also shows how the favorites function works in Voyant. To track several related words, use the search function in Words in the Entire Corpus, then select the word and hit the favorites heart in the bottom bar. Then you can toggle back and forth from favorites and search to either look at the list of words you want to track or select more words. From here, you can select one or more words from the favorites list to track visually chart their progress across the corpus. This is very handy tool for tracking word correlation and relation.

If you are interested in looking into these runaway trends in Voyant more closely, follow this link to a saved Voyant skin containing all of the collected ads from Texas, Arkansas, and Mississippi.